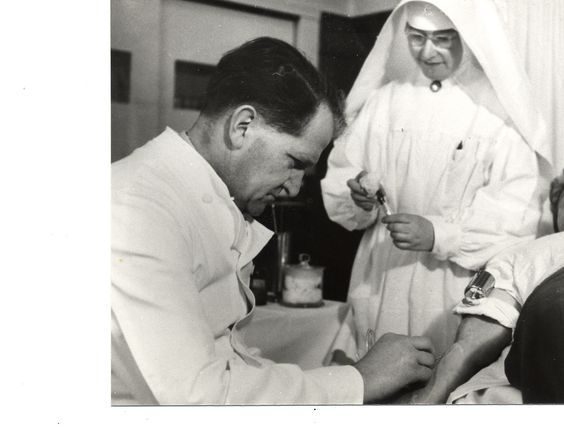

Gerhard Kreijen, 1952

Gerhard (or Gerd, Gerard) Kreijen (Kreyen) was a surgeon and gynecologist at St. Joseph‘s Hospital in Kerkrade.

In the story below, he played an important role as a negotiator, along with Pierre Schunck, the husband of his cousin Gerda Schunck-Cremers. That’s why it is extensively quoted from:

Het geluk van Limburg (The happiness of Limburg) by Marcia Luyten

p. 128

De Bezige Bij, ISBN 9789023496250, € 19,90

http://www.volkskrant.nl/boeken/meeslepende-geschiedenis-van-de-mijnstreek~a4191200/

An exciting book, although you might not expect that from a “history book”. It tells the story of the mining industry in Limburg and the family of Jaques (Sjakie) Vinders.

This story is set in September 1944. The Allied advance

stagnated on the Siegfried Line, the western defensive wall of over 600 kilometers along the German border that extended as far as the Netherlands and separated the Nieuwstraat from the Neustraße right through double city of Kerkrade/Herzogenrath. Thus Kerkrade became a front city. The western part, with Heilust and Spekholzerheide, was liberated by the Americans on September 17th, just like nearby Heerlen. The eastern part of Kerkrade, behind the Miljoenenlijntje (the 12-kilometer-long railway line between Schaesberg and Simpelveld, which had cost 1 million guilders per kilometer during construction), became a front line. First the residents were in their cellars for a week, while cannonballs, mortars and grenades exploded around them. Tap water was no longer there, power lines were broken and the last food had been done for days. The liberators were within reach and awfully far away. The Germans did not just give in. On September 13 they went to coal mine Oranje-Nassau 1. They filled the turbines of the power plant one by one with explosives and blew them all up. The above-ground part of the mine was virtually destroyed. The same happened at the mines Emma, Maurits and Julia. More than 85 percent of the energy supply in the Eastern Mining District was blown up. The residential areas of Kerkrade-East had to become a German fortress that had to reinforce the Siegfried line. On September 25, Kerkrade East was told that they had to evacuate their houses. The order to evacuate came at 4:30 am, and the city had to be delivered empty at noon. Mayor Habets, who resigned in 1941, returned to organize the evacuation. A column of 30,000 people marched on the only main road that the Germans had released, to Ubachsberg and Wijlre.

It was a column like from an African war. Lean, shaky families, with cattle on a rope, bags on their backs and pushing what they could transport on a cart, on the run for violence. People in hiding joined the procession, including Jewish people who saw the open air again for the first time in years. They breathed powder fumes. When the bombing broke out, the procession was still en route. Parents threw themselves at their children.

The only people left behind in the neighborhood were the patients and staff of the St. Joseph Hospital. They couldn’t leave. The Germans had seized the ambulances long ago. The fighting erupted and the hospital was at the epicenter of the shelling. After a night and a day in the line of fire, those who stayed behind decided to leave. Hundreds of patients, some of whom were just operated, pregnant women and women who had just given birth, were carted to Kerkrade-West on hospital beds and even wheelbarrows in which mattresses had been placed. Nurses and doctors pushed the patients while the Germans threw grenades at them. The last German left Kerkrade on 5 October 1944. Two weeks later, the citizens of Kerkrade returned to their liberated but broken city. 240 American soldiers had given their lives there. As a thank you, the square Ambachtsplein was renamed 0ld Hickory PLein, after the 30th Infantry Division Old Hickory of the US Army.”

Dr. Christine Schunck: “After the US army had liberated Valkenburg and Heerlen in late September 1944, their advance was stopped near Kerkrade. The Germans forced the entire population of 30,000 souls to leave the front area. Only the patients were still in the basement of the hospital. Gerd then contacted Pierre Schunck in Valkenburg Head of the resistance there) and they negotiated together with the occupiers to to open a corridor for some hours that would allow to bring the patients away with Pierre’s vans and anything that had wheels. The Kreijen family lived in our house for about two months. During that time, Gerd worked in the temporary hospital in Hotel Franssen in the now liberated Valkenburg, until they could return to Kerkrade.

bidprentjes archief rijckheyt.nl

Gerd/Gerhard Kreijen